The Lonely Hearts Scam

Today we’re used to people being conned or “catfished” by falling for someone they unwisely “meet” through social media, though the old term “lonely hearts” is still used to describe this kind of cruel deception.

The term originated when people would write what we’d know today as their “profiles” and send them, alongside their home address, to be listed in special columns of newspaper and magazines, with the plan to start a romance (or just a friendship) via letter-writing.

In 1950, a scam like this happened in Hollywood when Mrs. Claude J. Neal, 55, was conned by George Ashley into signing checks for $17,500. Ashley said he wanted the money for a deposit to buy the El Patio (now the shuttered Emerson Theatre), and promised her a job as hostess.

Though the married Neal said she had only joined the newspaper club to find friends, she did spend time with Ashley – though always denied there was any romance between them.

Either way, Ashley called her a “North Carolina hillbilly,” and once pulled out a gun and told her he didn’t want any more “monkey business.” Humiliated and ashamed, Neal finally went to the police after a frightening trip Ashley took her on to Nichols Canyon, where he pointed down the steep cliff and said:

“If I pushed you off there wouldn’t be one chance in ten thousand that your body would ever be found. Now, baby, you’d better fly right.”

Neal was one of an unlucky 13 woman who testified against Ashley and his co-defendants. Another of the victims was Ashley’s own wife, who was now suing him for divorce. No wonder the Los Angeles Herald-Express nicknamed him “Lord of Lonely Hearts.”

Swimming To Heaven (or Hell)

There are several notable historical stories of people going to a beach – or even out on a sailing vessel – and never being seen again. One of those happened here in Los Angeles, but in this case, it seemed the missing husband came back from the dead. Well, not quite.

On June 1928 the LA Times reported that Ferdinand Albor had been arrested in San Pedro for burglary. Police linked him to a smelter who had recently been nabbed for handling stolen gold and silver, and it emerged that Albor had been part of a San Francisco-based gang, but moved his operation to Los Angeles a year or so before.

There didn’t seem to be anything unusual about this until, a few days later, it was reported that K.L. Baumgartner, whose clothes had been found on a beach in Venice, California, some four years ago, had come back from the dead.

Albor the burglar had confessed to police that he was in fact Baumgartner:

“I was not drowned in the ocean, but fled because of an inner force that keeps me moving whether I really want to stay or not.”

Unhappily, Baumgartner’s wife – who had only been with him for four months before he “disappeared” – had remarried in the meantime, and, in a twist that seemed similar to the plot of the Irene Dunn/Cary Grant movie My Favorite Wife, she now needed to obtain an annulment and re-marry her new husband, a process that would take at least a year.

Baumgartner/Albor told detectives that he had received a head injury while working in the Seattle shipyards during WWI and “since then, I have not been wholly able to control my actions.” He and his wife had once owned a restaurant on Main Street in downtown L.A., but one day he “felt an irresistible urge to leave,” and he had worked as a cook in logging camps and “other out-of-the-way places” ever since.

An odd meeting between the Lazarus-like Baumgartner and his remarried wife took place in the County Jail, with Baumgartner whispering “How do you do?” before their awkward conversation began. He pledged to help her “regain her freedom,” while the shell-shocked woman simply told reporters that she and her new husband Robert Busby were happy together.

April Fools’ Day – sometimes the joke is on you…

It’s still a tradition amongst the mass media to plant a seemingly-false story on April Fools’ Day. Many places collate all their strange stories from the year so far, and then report them all on April 1 just so that readers (and their rival colleagues) can guess which one is the fake.

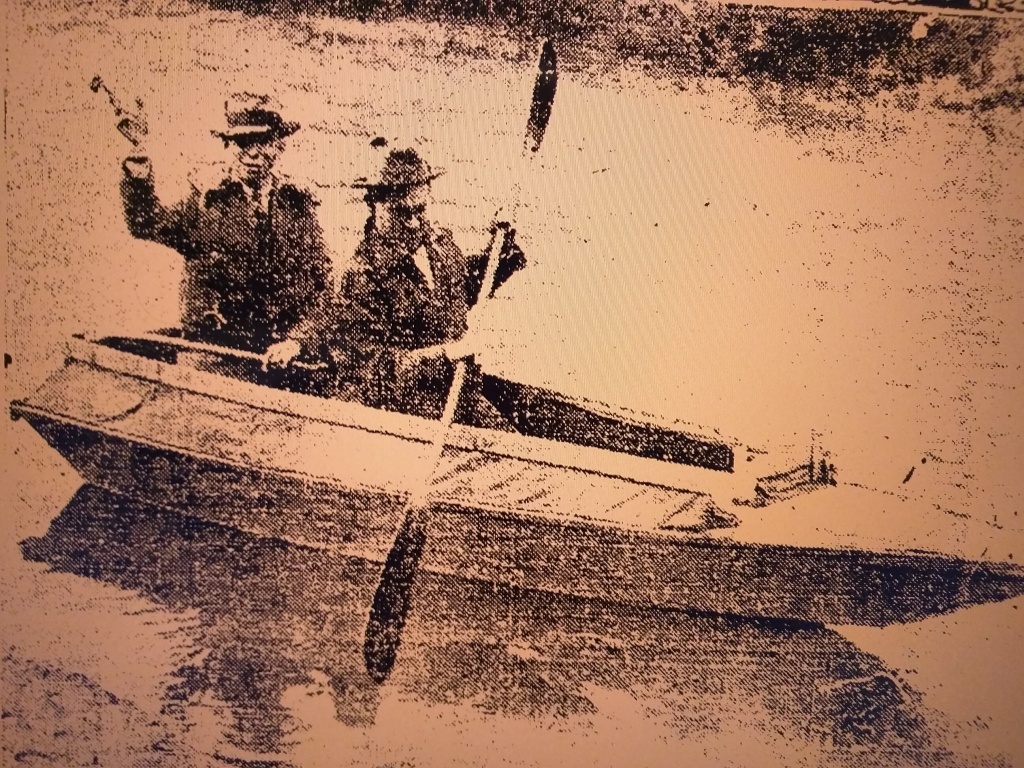

On April 1, 1925, a fun picture showed two suited men – a kayaker and an LA Times reporter – navigating a kind of kayak along the Los Angeles River, which at the time was more known for floods, pollution, and anything other than what we’d think of when we hear the word “river.”

Ironically, the joke turned out to be on the jokers. In 2008 a group of kayakers did indeed navigate the 51-mile concreted urban river, and paddlers can now indeed travel small sections of the L.A. River – it’s great fun. The cleaned-up L.A. River is now at the center of a huge, billion-dollar scheme to revitalize whole stretches, and the future should be a whirl of bike lanes, fishing, parks, sports, eateries and more.